- Assumptions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Characteristics of an Efficient Market

- Theories of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

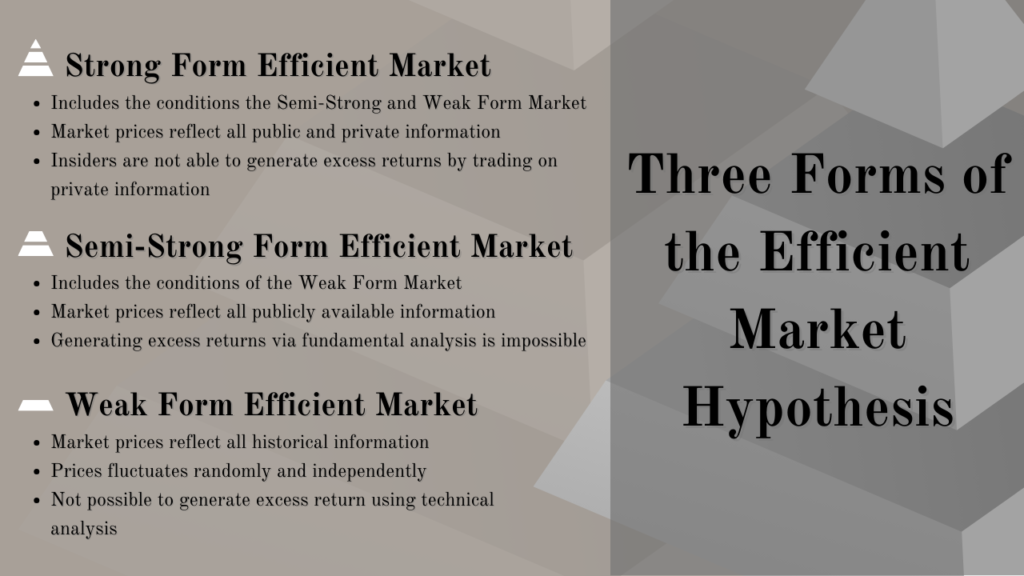

- Three Forms of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Some of the Arguments Against the Efficient Market Hypothesis

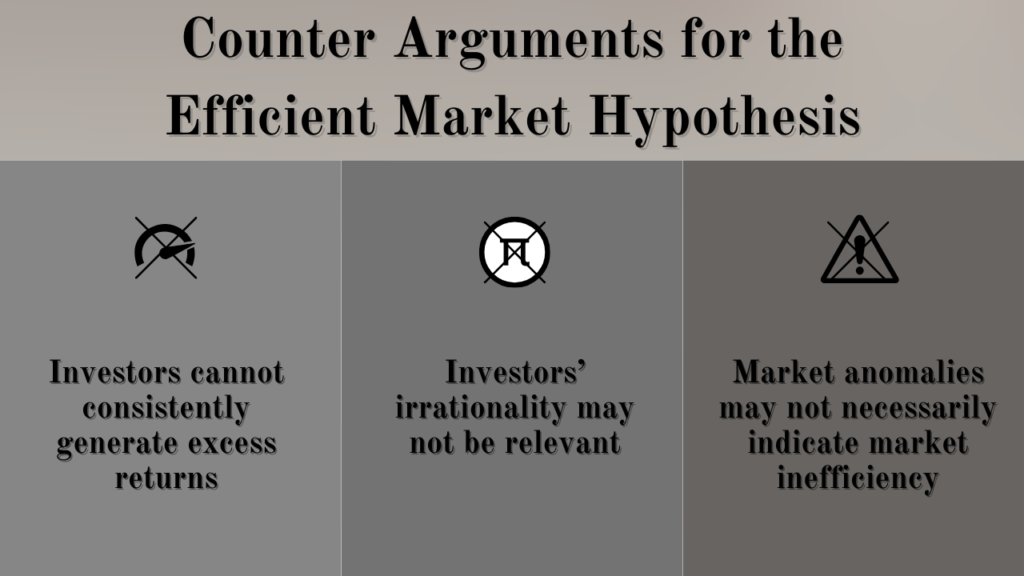

- Counter Arguments Defending the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Concluding Remarks

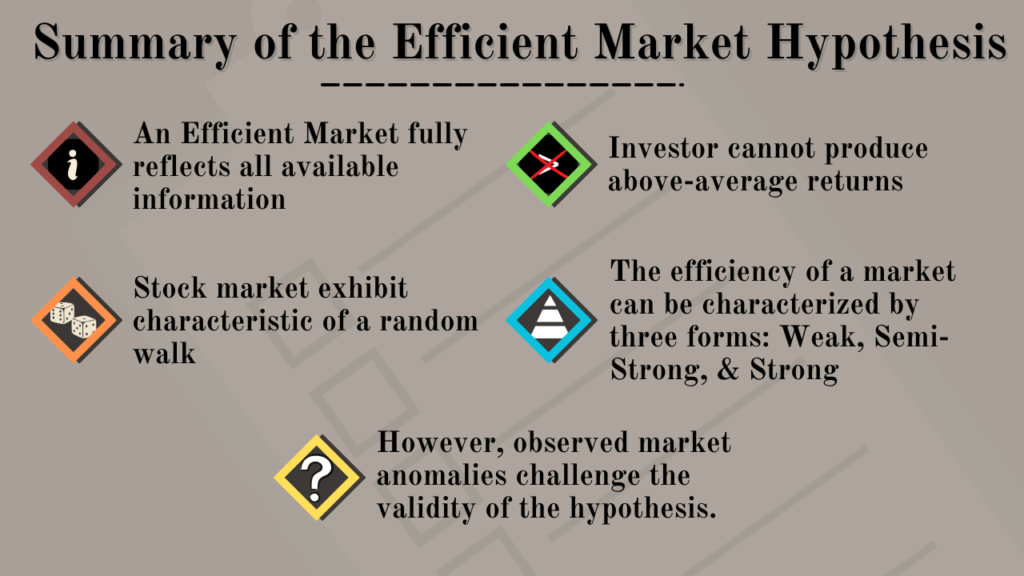

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) suggests that the market efficiently absorbs and reflects all available information, accurately determining a company’s true value at any given moment.

In an efficient market, investors can trust that the stock prices accurately represent all relevant market information at any point in time.

This theory operates on the assumption that the market consistently functions efficiently. Therefore, a stock’s market price is often considered its intrinsic value, with fluctuations reflecting changes in the company’s fundamentals.

Assumptions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

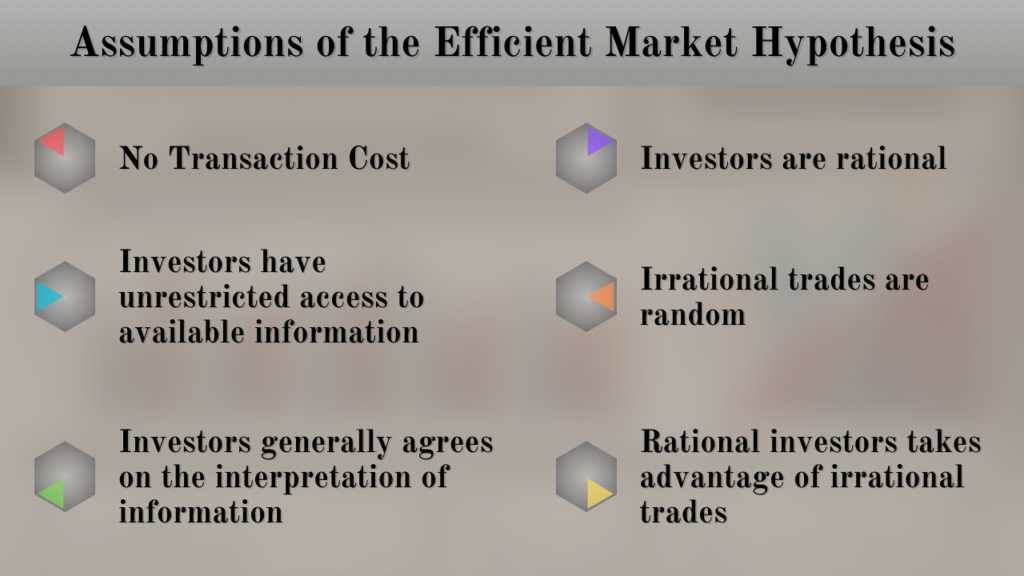

In 1970, Fama proposed criteria for an efficient market:

- There should be no transaction costs.

- All market participants should have unrestricted access to available information.

- Investors should generally agree on how to interpret this information.

Building on Fama’s work, Shleifer (2000) and Naseer and Tariq (2015) added:

- There should be no transaction costs.

- All market participants should have unrestricted access to available information.

- Investors should generally agree on how to interpret this information.

However, Fama (1970) understands that these conditions may be difficult to fulfil. They suggested that the market can still be considered efficient if:

- A sufficiently large investor meets these criteria

- Differing opinions don’t necessarily indicate market inefficiency unless there’s consistent evidence of investors outperforming the market by having a unique information evaluation technique

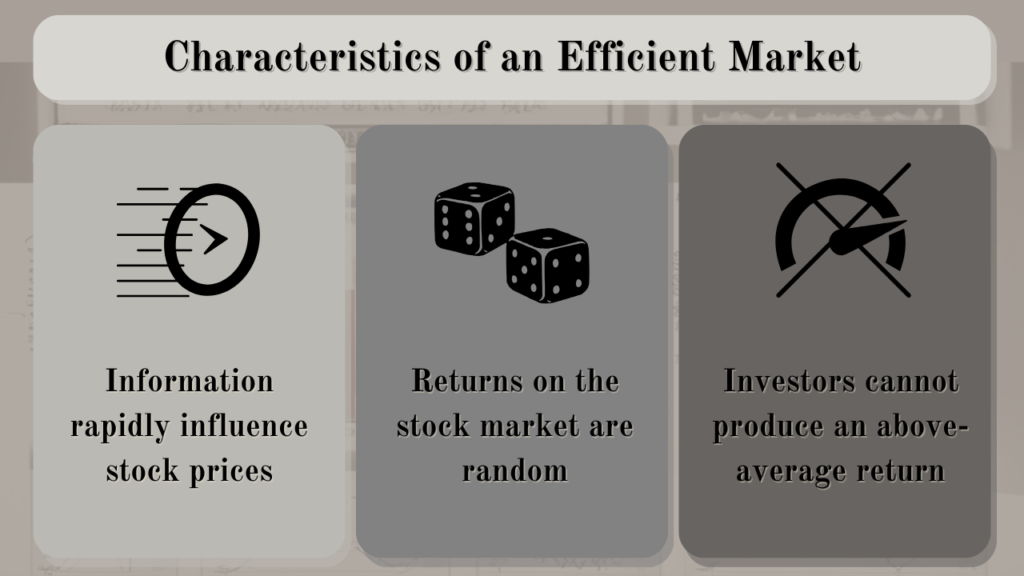

Characteristics of an Efficient Market

Information is immediately incorporated into security prices upon its release

In an efficient market, information immediately influences security prices upon its release. This means that all relevant information is incorporated into the security prices as soon as it is available.

Stock return in an efficient market is random

Since all important information is already factored into the stock prices, and future market developments are unpredictable, stock returns in an efficient market are considered random.

Investors cannot produce an above-average return

Given that stock prices reflect all available information and market returns are unpredictable, neither technical nor fundamental analysis can assist investors in achieving above-average returns.

Theories of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Fair Game Model

The Fair Game Model states that investors earn returns consistent with the level of risk they take on.

It suggests that because markets quickly incorporate all available information into prices, investors cannot reliably predict future market movements.

Submartingale

A submartingale describes a sequence of asset prices where each subsequent price, on average, is equal to or greater than the previous one.

This suggests that in an efficient market, investors cannot reliably predict future price movements based solely on past prices, as the expected future price tends to be higher or equal to the current price.

In essence, a submartingale reflects the idea that asset prices in efficient markets exhibit a tendency to increase or remain stable over time, but it doesn’t guarantee specific price movements in the future.

Random Walk

Stock prices in an efficient market are also described to be random and independent of the previous prices, a characteristic of the random walk.

As the efficient market is assumed to have incorporated all available information and the content of future information is unpredictable, any changes in tomorrow’s prices are solely due to information received tomorrow, and the price changes that follow should also be unpredictable and random.

Three Forms of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

An efficient market can be distinguished into three forms based on the level of information reflected in the market: weak form, semi-strong form, and strong form.

Weak Form Efficient Market

In a weak form efficient market, security prices are determined solely by historical data. This means that the current prices of securities already incorporate all historical information related to the stock.

Following the random walk hypothesis, security prices in a weak form efficient market fluctuate randomly and are unrelated to previous prices.

Consequently, attempting to earn an excess return through historical trend analysis (technical analysis) strategies is not feasible.

Semi-Strong Form Efficient Market

A semi-strong form market includes the conditions of the weak form efficient market, along with the assumption that market prices reflect all publicly available information.

In such a market, security prices incorporate all publicly available information, including earnings reports, dividend announcements, stock splits, new issues, as well as economic and political events.

Given the efficiency of a semi-strong form efficient market in incorporating all publicly available information, generating excess returns through fundamental analysis becomes theoretically impossible.

Strong Form Efficient Market

In a strong form efficient market, which includes the conditions of both semi-strong and weak form efficient markets, all available market information is fully incorporated.

This means that no individual possesses monopolistic access to any market information since the market reflects both public and private information.

Since the market has already incorporated all publicly and privately available information, it is not possible for investors to generate an above-average return from insider trading.

However, it is worth noting that Fama (1970) clarified that these assumptions may not be an accurate reflection of the stock market in reality. Instead, they suggest that the strong form efficient market should be viewed as a theoretical benchmark against which the market’s efficiency can be evaluated.

Some of the Arguments Against the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Arguments Against the Forms

Arguments against the Weak Form Efficient Market

Some authors, such as Naseer and Tariq (2015), Lo and MacKinlay (1999), and Degutis and Novickyte (2014), have challenged the assumption of randomness in stock prices, as suggested by the Weak Form Efficient Market theory.

There is evidence suggesting that investors are able to earn excess returns by analyzing historical stock price data, a strategy known as technical analysis.

Other studies have also noted a lack of evidence supporting the idea of a random walk in stock market returns, suggesting that the market returns might follow a predictive pattern.

Arguments Against the Semi-Strong Form Efficient Market

If the assumption that all publicly available information would be incorporated into the stock prices upon release holds true, one would expect to observe changes in securities’ prices upon the release of new information.

However, studies by Ball and Brown (1968) and Laidroo (2008) have shown that the publications of earnings do not appear to lead to any abnormal market movements. Specifically, research has revealed observed lags in market responses to new public releases.

Ball and Brown (1969) suggest that these observations could be due to:

- Anticipation of other finalized reports or corporate events that may be released concurrently with earnings publications

- The release of the annual report is a lag event, occurring only after the financial year has concluded

- Because it is a lag event, the market may have already adjusted to the expected performance of the firm

Arguments Against the Strong Form Efficient Market

As Fama (1970) pointed out, the idea of a market efficiently incorporating all available information may not accurately reflect real-world markets.

Syed and colleagues (1989) have suggested that trading on insider information could provide investors with an advantage in earning excess returns.

Furthermore, individuals outside of a company may also have access to non-public information. Lawyers, journalists, and other professionals may possess material non-public information, which they could leverage to generate returns that outperform the market.

Arguments against the Assumption of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Investors are not rational

Naseer and Tariq (2015) and Kahneman and Riepe (1998) have also suggested that humans are not always rational and are prone to errors in judgment. Biases such as overconfidence, optimism, risk aversion, and regret could influence an individual’s decision-making process, leading to irrational choices.

Even if the assumption that all investors are rational is true, Shiller and colleagues (1984) argued that individual investors may have limitations in modeling asset prices. Given this limitation, their evaluation methodology could be driven by social factors.

Investors’ irrationality also contributes to the price movements

Irrational trading decisions can significantly impact market price fluctuations.

Investors’ tendency to overreact to new information, whether positive or negative, can lead to excessive deviations in market prices (De Bondt &Thaler, 1985).

Irrational trades are not random and their influence on prices does not offset

Because individual investors’ evaluation methodologies can be influenced by social factors, investors may collectively execute similar trades on the same security at the same time.

Shiller and colleagues (1984) and De Bondt and Thaler (1985) have also demonstrated that investors tend to overreact to consensus opinions. Instead of witnessing equal levels of over-pessimism and over-optimism reactions, it is more likely to observe the market heavily favoring one opinion, resulting in price movements in a single direction.

Arguments against the assumed Characteristics of the Efficient Market

Information does not travel fast enough

Critics of the Efficient Market Hypothesis argue that the market does not immediately adjust to and incorporate new information.

While Scholes (1972) reportedly found that it takes around six days for the market to adjust to new information, others suggest that the market may not fully incorporate this new information entirely.

Market Anomalies suggest that stock prices are not random

Market anomalies, like the January Effect and the Day-of-the-Week Effect, provide evidence that there are consistent patterns in stock market returns.

The month of January has been shown to have an unusual return for the stock market. Similarly, increased trading volatility on certain days of the week has been found to generate excess returns (Malkiel, 2003; Naseer & Tariq, 2015; De Bondt & Thaler, 1985; Farooq, Bouaddi, & Ahmed, 2013).

Investors are able to earn above-average returns

Investors have utilized various evaluation methodologies, including Dividend-Yield Valuation, Price-Earnings Valuation, Price-to-Book Valuation, and Firm’s Size Valuation, to generate excess returns (Malkiel, 2003; Naseer & Tariq, 2015; Campbell & Shiller, 1988; Fama & French, 1992).

Similarly, the Momentum Strategy, which involves buying historical winners and selling historical losers, has proven to be an effective trading strategy in the short- to medium-term (Naseer & Tariq, 2015; Hon & Tonks, 2003).

Counter Arguments Defending the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Investors cannot consistently generate excess returns

Trading strategies based on the Calendar Effect, Seasonality Patterns, and Momentum may not be reliable.

Malkiel (2003) and Naseer and Tariq (2015) have questioned the reliability of the January Effect, noting its lack of consistency over time and its tendency to vanish shortly after discovery.

Others have demonstrated that transaction costs and mean reversion can eliminate any excess returns generated from the Momentum strategy (Fama, 1970; Naseer & Tariq, 2015; Malkiel, 2003; Odean, 1999).

Furthermore, some market anomalies may be a result of data mining and might have never existed in the first place, a false positive (Malkiel, 2003).

Additionally, Malkiel’s (2003) research has demonstrated that professional fund managers struggle to consistently outperform the broad market.

Investors’ irrationality may not be relevant to the efficiency of the market

Malkiel (2003) suggests that, while not all investors act rationally, their limited numbers and influence on the market make their behavior insignificant, alleviating concerns about its impact.

Firm’s Size Premium does not necessarily indicate market inefficiency

Fama and French (1996) found that the beta alone isn’t sufficient to explain all variables affecting stock returns. They found that the size factor also influences returns.

Since the size premium was already factored into the market’s returns, Fama and French (1996) proposed that the firm’s size premium poses a challenge to the Capital Asset Pricing Model, rather than questioning market efficiency.

Price-to-Book Value Premium does not necessarily indicate market inefficiency

Additionally, authors like Malkiel (2003) and Fama and French (1996) suggest that the observed higher return from stocks that have higher book-to-market value may not be due to market inefficiency.

Rather, similar to the firm’s size premium, this observation could be due to the Capital Asset Pricing Model’s limitation of covering all variables contributing to the stock’s return.

Concluding Remarks

Given the numerous criticisms faced by the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), some authors argue that it shouldn’t be viewed as an exact portrayal of market behavior, but rather as a benchmark for understanding market dynamics under EMH conditions (Degutis & Novickyte, 2014; Naseer & Tariq, 2015; Fama, 1970).

Furthermore, Naseer and Tariq (2015) along with Malkiel (2003) recognize that errors in judgment are inevitable in the stock market. They suggest that market efficiency isn’t always guaranteed, as there needs to be room for professionals seeking excess returns to operate.

In assessing market efficiency, we encourage investors to exercise caution, critically evaluate the theory, and consider various perspectives.

References

Ball, R., & Brown, P. (1968). An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers. Journal of Accounting Research, 6(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490232

Barnes, P. (1986). Thin Trading and Stock Market Efficiency: the Case of the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 13(4), 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.1986.tb00522.x

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1988). Stock Prices, Earnings, and Expected Dividends. The Journal of Finance (New York), 43(3), 661–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb04598.x

Chong, T. T.-L., & Luk, K. K. (2010). Does the “Dogs of the Dow” strategy work better in blue chips? Applied Economics Letters, 17(12), 1173–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17446540902845495

De Bondt, W. F. M., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the Stock Market Overreact? The Journal of Finance (New York), 40(3), 793–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1985.tb05004.x

Degutis, A., & Novickyte, L. (2014). THE EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF LITERATURE AND METHODOLOGY. Ekonomika – Vilniaus Universitetas, 93(2), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2014.2.3549

Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. The Journal of Finance (New York), 25(2), 383-417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325486

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance (New York), 47(2), 427–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04398.x

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1996). Multifactor Explanations of Asset Pricing Anomalies. The Journal of Finance (New York), 51(1), 55–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1996.tb05202.x

Fama, E. F., Fisher, L., Jensen, M. C., & Roll, R. (1969). The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information. International Economic Review (Philadelphia), 10(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2525569

Farooq, O., Bouaddi, M., & Ahmed, N. (2013). Day Of The Week And Its Effect On Stock Market Volatility: Evidence From An Emerging Market. Journal of Applied Business Research, 29(6), 1727–1736. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v29i6.8210

Fluck, Z., Malkiel, B. G., & Quandt, R. E. (1997). The Predictability of Stock Returns: A Cross-Sectional Simulation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465397556764

Hon, M. T., & Tonks, I. (2003). Momentum in the UK stock market. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 13(1), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1042-444X(02)00022-1

Kahneman, D., & Riepe, M. W. (1998). Aspects of Investor Psychology. Journal of Portfolio Management, 24(4), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.1998.409643

Laidroo, L. (2008). Public announcement induced market reactions on Baltic stock exchanges. Baltic Journal of Management, 3(2), 174-192. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465260810875505

Lo, A. W., & MacKinlay, A. C. (1999). A non-random walk down wall street. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400829095

Malkiel, B. G. (2003). The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533003321164958

Naseer, M., & bin Tariq, Y. (2015). The Efficient Market Hypothesis: A Critical Review of the Literature. The ICFAI Journal of Financial Risk Management, 12(4), 48-63.

Odean, T. (1999). Do Investors Trade Too Much? The American Economic Review, 89(5), 1279–1298. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.5.1279

Scholes, M. S. (1972). The Market for Securities: Substitution Versus Price Pressure and the Effects of Information on Share Prices. The Journal of Business (Chicago, Ill.), 45(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1086/295444

Shiller, R. J., Fischer, S., & Friedman, B. M. (1984). Stock Prices and Social Dynamics. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1984(2), 457–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534436

Shleifer, A. (2000). Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198292279.001.0001

Syed, A. A., Liu, P., & Smith, S. D. (1989). The Exploitation of Inside Information at the Wall Street Journal: A Test of Strong Form Efficiency. The Financial Review (Buffalo, N.Y.), 24(4), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.1989.tb00361.x

Other Useful Readings

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1998). Valuation Ratios and the Long-Run Stock Market Outlook. Journal of Portfolio Management, 24(2), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.24.2.11

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1988). Permanent and Temporary Components of Stock Prices. The Journal of Political Economy, 96(2), 246–273. https://doi.org/10.1086/261535

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973). On the psychology of prediction. Psychological Review, 80(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034747

Niederhoffer, V., & Osborne, M. F. M. (1966). Market Making and Reversal on the Stock Exchange. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 61(316), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.2307/2283188

Varvouzou, I. (2013). Capital market anomalies explained by humans irrationality (1st ed.). Anchor Academic Pub.